The Vacillating Imagination of “us” in Black Panther (2018)

Abstract

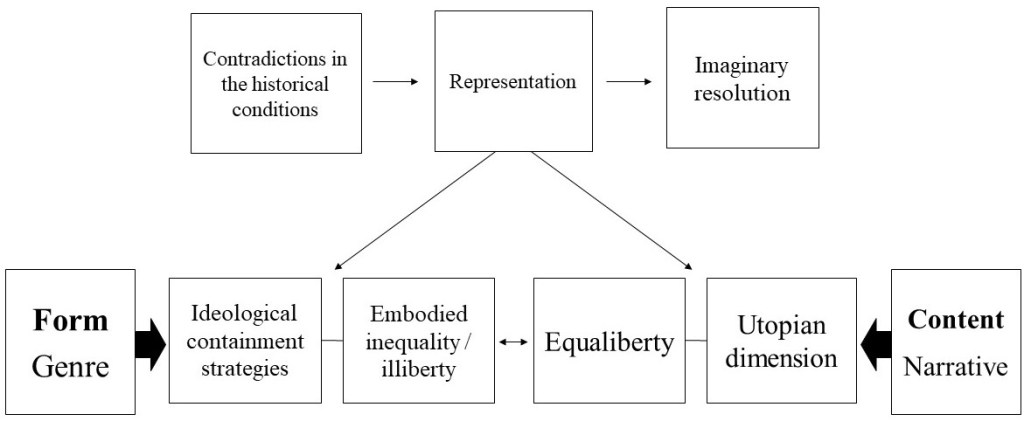

This article analyzes the cultural politics of the vacillating imagination of “us” represented in Black Panther, released in 2018. This popular cultural text centralizes Blackness in that it refers to instances of Black oppression in the early 1990s. Amid the contradiction between the film’s Black-centered content and the form of the Hollywood superhero genre, the imagination of “us” in the film expands and shrinks. Drawing on concepts developed by Fredric Jameson and Étienne Balibar, including imaginary resolution, utopian potential, ideological containment, and equaliberty, this article critically examines the ideologies in the text. When it comes to the expansion of “us,” the article explores the utopian potential in the representation of the radical villain. In terms of the shrinkage of “us,” it investigates the function of ideological containment in the Hollywood superhero movie by focusing on the representation of the hero, and the portrait of South Korea as a spectacular background.

Into the text

Figure 1. Theoretical framework for ideological critique

“While transcending national or ethnic identities, Blackness itself is deconstructed in a transnational way. In this scene, Blackness carries a new utopian possibility of being reconstructed into an anti-racial concept that can destroy all premises of racist narratives and racial inequalities. This scene gives a glimpse of a powerful potential utopian element of universal “equaliberty” in that it shines like a flash of light toward liberation from racial economic inequality for everyone, not Black people only.” p.11

“The contradiction inherent in the behavior of this good hero paradoxically implies that the superhero genre has given T’Challa the power to determine – and even destroy – the rules arbitrarily. In this sense, not Ross, but T’Challa serves as an allegory for the political unconsciousness of the power strategy of the US, which has the power to determine the rules and the boundary of “us” arbitrarily.” p.13

“In this sense, the film portrays the city as only a spectacular backdrop by either visualizing a fictional tourist attraction, like the casino, or selectively adopting actual tourist destinations. The concrete Korean landscape is depicted in splendid detail, but the connection between Korea and the history of Black oppression vanishes in terms of the abstraction of the totality of racial capitalism. Consequently, the distance between Koreanness or Asianness and Blackness becomes even greater in this context.” p.15